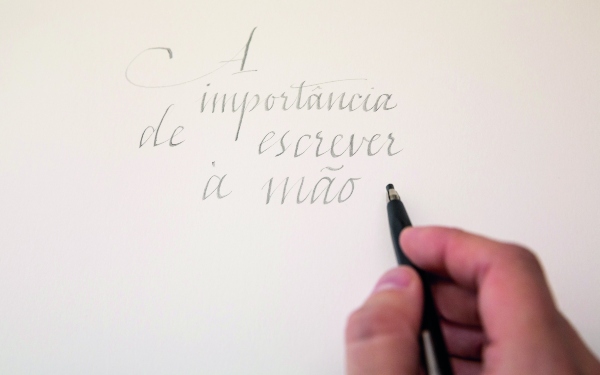

Everything changed with Gutenberg’s invention in the fifteenth century. And it changed again with the typewriter, in the second half of the nineteenth century. And once again with the computer, in the mid-twentieth century. Today, with our feet firmly in the third millennium and technology all around us and in our pockets everywhere we go, writing by hand is still an essential skill, one that affects us as people from the moment we learn to write our first letter.

“Writing by hand is important, especially at a particular stage in life, when we start to acquire writing skills,” explained Nuno Leitão, headteacher at Cooperativa de Ensino A Torre. “Because writing is a mental act, in which the body also takes part. There is a clear connection between hand and brain, which enabled the specific development of the human species.”

Marta Gonçalves, an educational psychologist, added that “writing by hand influences sight-motor coordination in a different way from writing on a keyboard, as it works different skills,” and that “handwriting does much more to develop fine motor skills”.

Writing by hand, forming words, involves the mind and requires structured thought. It activates our brain as a whole, which is why we have better recall of things we write down, and helps us to develop vocabulary and spelling. It has an important cognitive function and, according to Nuno Leitão, a metacognitive function too: “Handwritten text is much less automatic than at a keyboard. More thought, more feeling goes into it. The substance of what I have to say is more creative when I write by hand. What I want to convey is more deliberate.”

The art of drawing letters

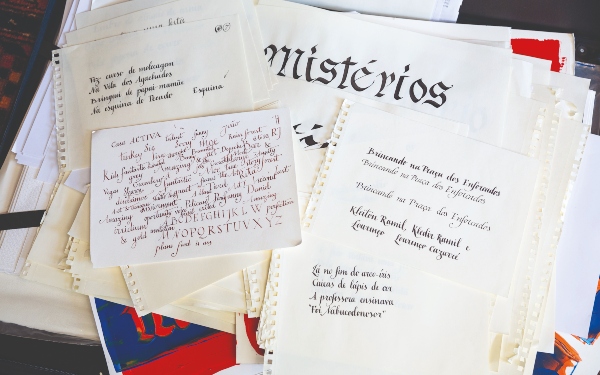

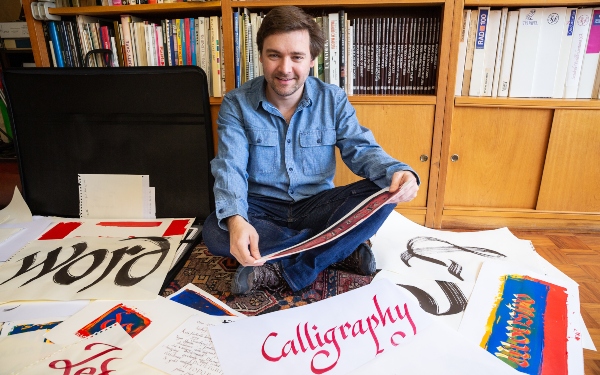

The word calligraphy is formed from two Greek words, kalli, meaning beauty, and graphẽ, meaning writing. So it means, literally, “beautiful writing”. Before the invention of the printing press, calligraphers were copyists, with immaculate handwriting, who transcribed books. This enabled knowledge to be stored, in legible writing that was easy on the eye. “When copying a book, the copyists wouldn’t use their everyday handwriting,” explained João Brandão, a calligrapher. “With printing, that all disappeared, and the calligrapher moved from being a copyist to a kind of artist,” he tells us.

A graphic designer by trade, João Brandão developed an interest in calligraphy because of the close connection between his work and typesetting. He has now completely changed his everyday handwriting and, although he is a fierce advocate of writing by hand, “with all the advantages in terms of neurological development and fine motor skills,” he argues that “the handwriting that children are taught is too complicated and not very efficient.”

“The writing that children are taught at school, the so-called ‘primary school writing’, is derived from copperplate, which is a style we find in the documents prepared by copyists before the invention of printing. It’s very attractive, but very difficult, and not at all the most legible style,” he says. He is an advocate of italic – the script he has adopted for himself and taught his son when he was nine years old – and argues that it is simpler and more effective. “It’s a style that uses very specific techniques, created for performance, speed and efficiency. It’s a cursive, joined-up script, and was originally created to be fast, as the nib is raised from the paper as little as possible. And it has none of the ornaments of the style derived from copperplate which is taught in schools, which is actually a script where distinguishing between certain letters is not easy.”

Nuno Leitão also spoke about the complexity of ‘primary school writing’. “Could the writing style we teach primary school children be simpler?”, he asks, and wastes no time in replying. “Yes. It would certainly be possible to find an easier and simpler script, without so much ornamentation, whilst still retaining handwriting as the initial stage in the learning of writing.”

But for children to learn only what is called printed characters or block letters is not enough. The educational psychologist Marta Gonçalves argues that “learning block letters alone is not enough to develop cognitive flexibility” and that “it’s important for children to recognise that there are several forms for the same letter.” Nuno Leitão told us that “block letters have the advantage of being what the children most see around them,” but it can’t be the only style, because it’s not cursive, “joining up the letters has advantages for motor skills and also cognitive skills: being able to write a word without lifting the pen from the paper, the fluidity creates interesting connections, with implications for thought processes.” He added: “In addition, and I say this more intuitively than scientifically, joining up the letters and writing the whole word enables me to centre more on the meaning of the word than on its spelling.”

My handwriting is better than yours

The learning process involves children learning to join up the letters, but handwriting also serves as a way to express your personality, as Nuno Leitão explained: “There’s a standard style, but then each of us arrives at his or her own handwriting. We appropriate what we learn for ourselves. In education, we have to insist that kids write legibly, but we shouldn’t go against their own appropriation of the alphabet. It’s positive for each individual to have his own writing style. More empirically, in what I see every day, the style of lettering reflects the type of mind; whether it’s a more down-to-earth, logical mind, or else more of a dreamer or poet.”

There is everyday handwriting, which is for everyone and, at the same time, specifically for each of us, and then there is calligraphy, which is more erudite, an art. “There’s a revival in these styles that were adopted for books in the past,” explained João Brandão. “People are coming back to hand made things. We live in a highly technological world, everything is industrialised, and people are getting tired of it, they feel the need for a counterweight. Even in design, calligraphy is back in fashion. You go to a supermarket and the prices are chalked up, all the slow food outlets have menus written by hand on a slate, there’s handwriting on t-shirts… calligraphy is enjoying a boom.”

Art or craft, even and refined or quirky and personal, handwriting and calligraphy remain fundamental to human development, and learning to write by hand is an essential stage in learning to read and write. From hand to brain and from brain to hand, in a never-ending circle, the word takes form on the blank sheet, expressing ideas and thoughts, intentions and emotions.

Writing by hand develops a number of associated skills. But calligraphy has a more artistic element, which not everyone can master.